Adapting health facilities

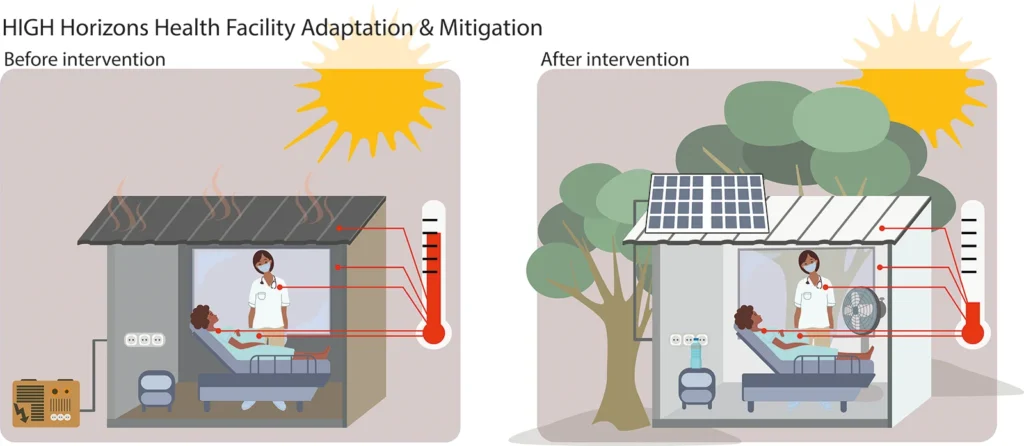

We are exploring how health facilities that provide maternal and newborn health care can adapt to beat the heat.

Beating the heat

As temperatures rise alongside worsening global warming, the task for health facilities to keep pregnant and postpartum women, children, and the health workers cool has never been more pressing.

The need for low-carbon, heat-resilient adaptation is particularly urgent for health facilities in lower-income or rural areas that are constrained by limited funds, and where energy-intensive cooling systems, such as air conditioning, are not possible.

“During labour and childbirth, there’s a very large amount of heat generated by the physical exertion. Many facilities [in low- and middle- income countries] offer very little, or even no, protection against heat”, said Matthew Chersich, a HIGH Horizons researcher from Wits Planetary Health Research at the University of Witwatersrand in South Africa.

He added: “The environment is not suitable to protect these women, and, in some places, there isn’t even water, let alone cold water. So you can have a ten-hour ‘marathon’ with extremely high temperatures”.

To beat the heat, we are working to identify affordable structural adaptations that can be made to maternity care facility buildings and grounds to lower temperatures both inside and outside, such as adding reflective paint to the roof, creating structures that provide shade, and installing building insulation and ventilation.

Protecting maternal and neonatal health workers

In addition to improvements to structures, we’re also researching what can be done in facilities to better support health workers, whose health is vital to providing quality care on maternal and neonatal wards, to cope with increasing temperatures.

Without proper adaptation for heat, rising indoor temperatures in facilities can exacerbate health worker fatigue, impact the care they provide, and compromise the health outcomes of patients. Ultimately, increasing heat can affect the quality of care provided in the facility, and the resilience of the health system as a whole.

“Heat is an occupational hazard, and that’s not something new. There have been many incidents of exhaustion and dehydration, in addition to the mental health issues in the long term”, explained Nasser Fardousi, a HIGH Horizons researcher at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine.

Working on a maternity ward in hot weather can be hugely challenging. As one South African health worker described their work when temperatures rise: “On days where we have 13 to 15 deliveries, it’s not like you have time to take many water breaks. You can become dehydrated or unwell”.

We are looking at interventions to protect health workers such as installing water stations to make it easier for workers to stay hydrated, and providing cooling vests to help keep workers from getting too hot.

Several facilities in Africa have already begun implementing some of these adaptation interventions, including maternity clinics and a regional hospital in the Tshwane region of South Africa, as well as the rural Mt Darwin region of Zimbabwe

Resources

Related Publications

- Project Deliverable: Toftum J, Sode Vest A, Mahdi-Waldorff A, Muronzie T, Luchters S, Parker C, et al. HIGH Horizons – Environmental exposures in health facilities. Zenodo; 2024 Jul.